Coronavirus

I’ve updated this entry from a couple of days ago, with some additional resources, and a few new personal refections.

I made a rather flippant post about the current coronavirus pandemic on Facebook last week, which some people appreciated for my attempt at humor, but others thought was being too dismissive of a potentially serious situation. A former high school classmate and fellow physician was one of the people who called me out on the latter, and I think she’s right, that my comments could be construed as being too nonchalant.

So, I deleted that Facebook post, about how America losing its collective mind being one of the complications of the coronavirus pandemic, and thought I’d post something that I hope is a bit more edifying. I still think my original post was kind of funny, and also has some interesting points to consider which I’ll return to later in this post, but first let’s deal with the serious stuff.

What We Know and Don’t Know

I’m not an infectious disease expert or epidemiologist, so what follows comes directly from more authoritative sources, such as the National Institutes for Health (NIH), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the World Health Organization (WHO). There is much we don’t yet know about this virus and the illness it causes. It’s a novel (new) coronavirus, now named SARS-CoV-2, and causes the disease we are now calling COVID-19, for “Coronavirus Disease 2019”.

Coronaviruses are common in humans and many animals, with the more typical human coronaviruses responsible for a usually mild upper respiratory infection which we call the “common cold” (rhinoviruses are an even more common cause of this condition). As with all viruses, coronaviruses are typically fairly species-specific, meaning a given version may cause disease in a human but not a cow, and vice versa. Every now and then, however, a given strain of virus will make the jump from one species to another, such as us humans, causing a new illness (which is called a zoonotic disease, meaning from-an-animal).

This particular coronavirus is thought to have arisen from bats, which was also true of the MERS-CoV coronavirus, which caused MERS, or “Middle East Respiratory Syndrome” in 2012, and SARS-CoV coronavirus, which caused SARS, or “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome” in 2003.

MERS originated in Saudi Arabia, and while it had a mortality rate of nearly 35%, which is much higher than what we are seeing with COVID-19, it fortunately did not spread much beyond the Arabian peninsula, excepting some travelers who had first become infected in the Middle East (so-called “imported cases”). The total number of confirmed MERS cases to date is only 2494, according to the WHO. SARS originated in China, like COVID-19, and was also a severe outbreak, with a mortality rate of nearly 10%, but it also didn’t spread too widely. The total number of confirmed SARS cases was 8096, according to the WHO.

There are still sporadic cases of MERS reported in the Middle East, transmitted from camels to humans (it is thought originally to have come from bats, then spread to camels). No cases of SARS have been reported since 2004.

CDC: Common Human Coronaviruses

There are a lot of different factors that determine whether an infectious agent is likely to cause a serious global health concern.

Agent factors include transmissibility (how easily it is transmitted from an infected host to an uninfected one), infectivity (how likely it is to infect a host if transmitted, which is partly a host factor, too), virulence (how likely it is to cause severe disease in an infected host, again also with a host factor), replicability (how fast and how many new infectious agents it can release to be transmitted further), and persistence (how long it can remain infectious in the environment and/or whether it has another host reservoir (like camels for MERS).

Host factors include resistance to infection (immunization from prior exposure or vaccination, and usually poorly understood genetic factors), susceptibility to severe disease (underlying chronic medical conditions and, again, usually poorly understood genetic factors), and behavioral adaptations (wearing masks, washing hands, etc.).

For COVID-19, we don’t yet know as much about any of those factors as we would like, but that remains largely true for SARS and MERS, as well. Based upon the fact that there are, as of this writing,153,648 confirmed cases worldwide, SARS-CoV-2 appears to be more transmissible and infective than either MERS-CoV or SARS-CoV. But, the good news is that it appears to be less virulent, with a current worldwide mortality rate of 3.7% for COVID-19, compared to 35% and 10% for MERS and SARS, respectively.

And, that reported mortality rate is likely higher than it is in reality, as it is thought probable that many asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic people who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 haven’t even been tested. Anthony Fauci, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Director at the NIH, estimated that the true mortality rate for COVID-19 may be as low as 1%, or even less, in a NEJM editorial last month. But, as he said in Congressional testimony two days ago, even a 1% mortality rate is still ten times more lethal than seasonal influenza, which typically has a mortality rate of around 0.1%. So, COVID-19 is concerning and does bear watching.

People who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 may remain asymptomatic, many will develop generally mild upper respiratory symptoms similar to what we experience with a common cold or seasonal influenza, and some will become severely ill and might even die.

Based upon what we know from reports of COVID-19 thus far, and from a long history with seasonal influenza, those most at risk for serious illness or death include the aged and/or those with significant underlying medical conditions, to include heart problems, lung disease, and diabetes. Mortality rates will be higher in poorer countries with less advanced healthcare systems, and lower in more developed countries.

NEJM: Covid-19 — Navigating the Uncharted

CNBC: Top US Health Official Says the Coronavirus Is 10 Times ‘more lethal’ than the Seasonal Flu

What You Should and Should Not Do

This early in the pandemic, we don’t know as much as we’d like regarding the ease of transmissibility of this virus or the most important routes of transmission, though respiratory is likely the primary mode. So, recommendations now may change as new data is available.

For now, wash your hands with soap and water, or use a hand sanitizer if you can’t wash your hands. Try to avoid touching your face (I know, that’s nearly impossible). Clean frequently touched surfaces at home and work regularly. Try to avoid touching surfaces in public spaces as much as possible, and if you have to, wash or sanitize your hands afterwards.

Maybe do an elbow bump rather than a handshake (as a former candidate, I find this hard). Avoid crowds and close proximity to others as much as possible (what we are apparently calling “social distancing”).

Probably most importantly, isolate yourself as much as possible if you feel ill. Cough or sneeze into your elbow or a tissue. Wear a mask around others. And, get tested; not only for COVID-19, for which I hope we’ll have abundant testing kits available soon, but also influenza and whatever else your healthcare provider might recommend.

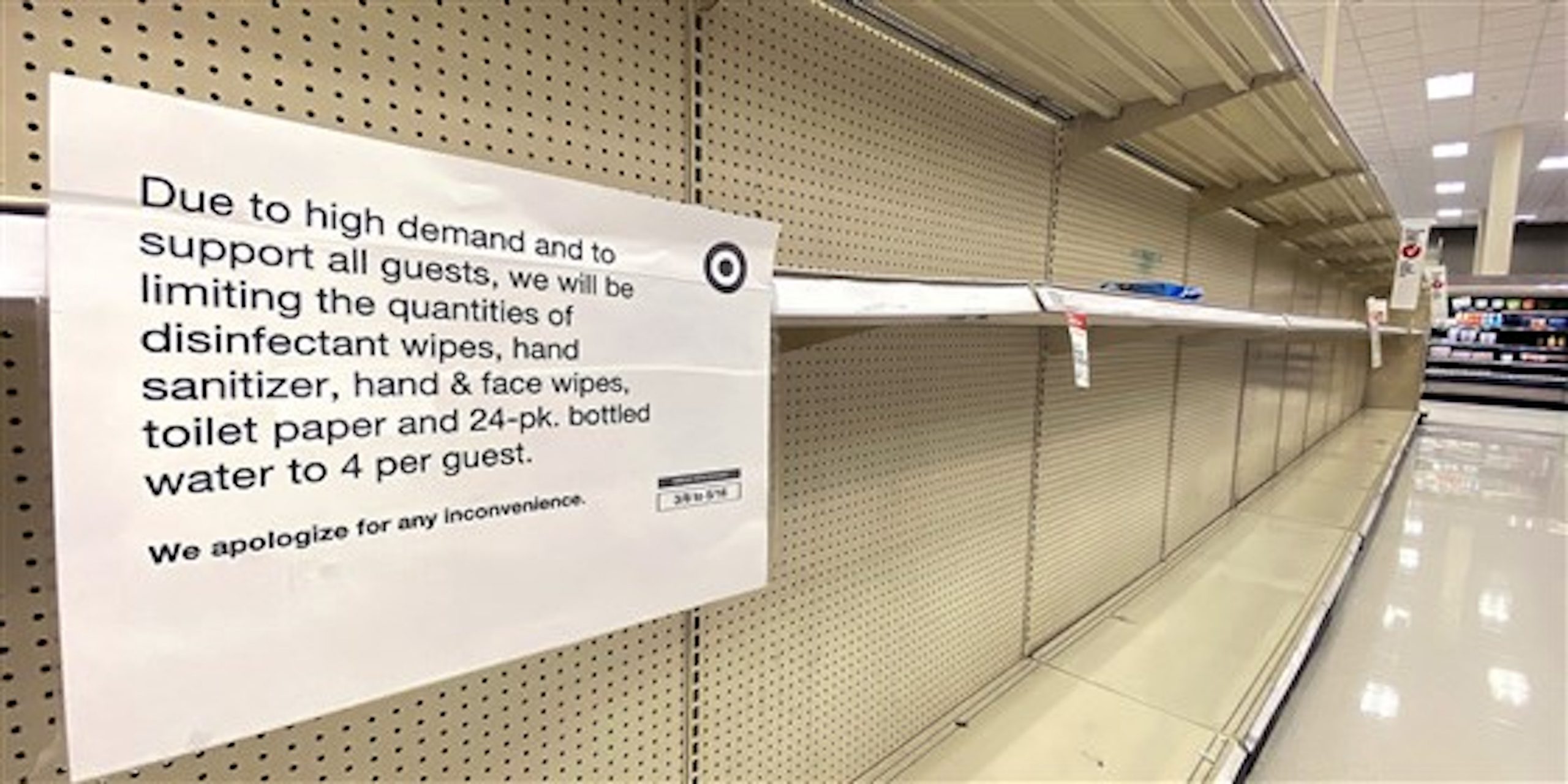

COVID-19 has the potential to be devastating on personal, societal, and economic levels, so being prepared as much as possible is prudent. But, buying more than you would need for a few weeks at home is not sensible, but selfish. Many people in our communities live paycheck to paycheck, and must purchase supplies as they need them. If the shelves are bare, they have to waste time and money to find what they need, or do without. And, buying in bulk with the hope of capitalizing on this pandemic is simply despicable, in my opinion. By the way, if you need more than two rolls of toilet paper per person per month, you might have a medical condition unrelated to COVID-19.

Don’t rely on social media for information, unless an article comes from a reliable source and cites references. Here are the WHO, NIH, and CDC websites for COVID-19 that I’ve been checking a couple of times a week:

World Health Organization COVID-19 Updates

Have We Lost Our Minds?

Yeah, I think so, at least a little bit.

A brief recap on COVID-19: So far, 153,648 confirmed cases worldwide, with 5,746 deaths, yielding a reported mortality rate of 3.7%, but likely closer to 1%. In comparison, seasonal influenza is estimated to cause 3 to 5 million cases of severe illness and 290,000 to 650,000 deaths worldwide each year. Each and every year, I will add. And periodic influenza pandemics have been even more deadly. No, COVID-19 is not the same as influenza, but I’m comparing the two for a sense of scale, which I find useful.

The 1918 H1N1 pandemic, commonly called the “Spanish flu”, though it may have actually originated in my home state of Kansas, infected an estimated 500 million people worldwide (over one-quarter of the population back then), causing at least 17 million deaths, and perhaps as many as 100 million. The 1968 H3N2 pandemic, known as the Hong Kong flu, because it did originate in Hong Kong, caused an estimated 1 million deaths worldwide. That one is personal to me, as I was affected; I developed a very high fever with seizures, and ended up on anti-seizure medication for several years thereafter.

Will COVID-19 cause more illness and death than our yearly seasonal influenza? It’s certainly seems possible, as Anthony Fauci pointed out to Congress. It has already severely strained healthcare resources in those areas that have been hardest hit, to include China, Italy, and Washington state. Or, will it be more like the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, known as the swine flu (even though it was a hybrid of swine, avian, and human influenza viruses), which in retrospect was determined to be less deadly than seasonal influenza, despite being labeled a pandemic? Perhaps, but we’ll have to wait and see.

Personally, I still think we may be overreacting, but I admit that I could be wrong. I’m married, so I know that happens. One cause for optimism, I hope, is that it appears that the number of new confirmed cases have declined markedly in China and South Korea. Again, confirmed cases does not mean everyone who was infected, just those who were tested and returned a positive result. Still the number of confirmed cases in China and South Korea was a fraction of 1% of the total population in each. That gives me hope that we’ll not see infection rates as high as 50% in America, as was recently reported to Congress.

The Upside

But, even if we are overreacting, we are going to realize some benefits, both in terms of lives saved and healthcare resources preserved. As with China and South Korea, I hope we will also soon “flatten the curve” of new cases because of our efforts. There will be consequences, particularly economic ones, as we’re already seeing, but perhaps that’ll be a worthwhile tradeoff in the long run.

Another positive in our response that I hope we realize is a boost in future preparedness. As a surgeon, and particularly during my Army days, we did periodic drills to simulate what we might expect to see in a mass-casualty situation. I honestly don’t think those were as valuable as senior officers perhaps believed, but it did get you thinking about what you could need and how you might get it.

Even if COVID-19 turns out not to be as severe as some are predicting, going through this exercise should be of value to us in the future. Because a serious global pandemic, 1918-style, is only a matter of when, not if. I hope we will all be better about personal hygiene (I see some of you men leave restaurant restrooms without washing your hands, and that’s just nasty), practicing social distancing when necessary, self-isolating when ill (to include support for employees who must take off from work), beefing up our healthcare system (ICU beds, ventilators, personal protective gear, and personnel), streamlining our ability to get diagnostic tests where they need to be promptly, and even better international communication (I’m looking at you, China, both with COVID-19 and SARS).

Finally, bear in mind that we’ve only been discussing respiratory diseases due to coronaviruses and influenza viruses. There are a whole host of nasty microscopic critters, viral and bacterial, out there that would be happy to take advantage of our very mobile and highly social species. We’re also a intensely connected species nowadays, and I think that’s part of our mental health problem as regards this pandemic.

We are a resilient species and we’ll get through this. We’re collaborative, generally empathetic, and for the most part, fairly intelligent.

Unfortunately, we’re not always seeing the best in ourselves at the moment. Selfish hoarding, excessive panic, and sharing false or misleading information are not helpful. I’ve seen people claim COVID-19 is bioterrorism, not due to a natural occurring virus. Some have speculated that it’s a false-flag operation by our own government, with the goal of further eroding our civil liberties. Some have claimed that the media is hyping this crisis to undermine President Trump. One person claimed that it’s not a virus at all, but due to heavy metals and that we simply need to detox, or something of the sort.

Yes, I think we have somewhat lost our minds, and much of that has to do with our hyperconnected world. Sensationalism over substance. Opinion rather than facts. Fake news and conspiracies.

I hope we can do better going forward. In the meantime, stay safe, don’t panic, and for goodness sakes, wash your hands!

Washington Post: Why Outbreaks Like Coronavirus Spread Exponentially, and How to “Flatten the Curve”