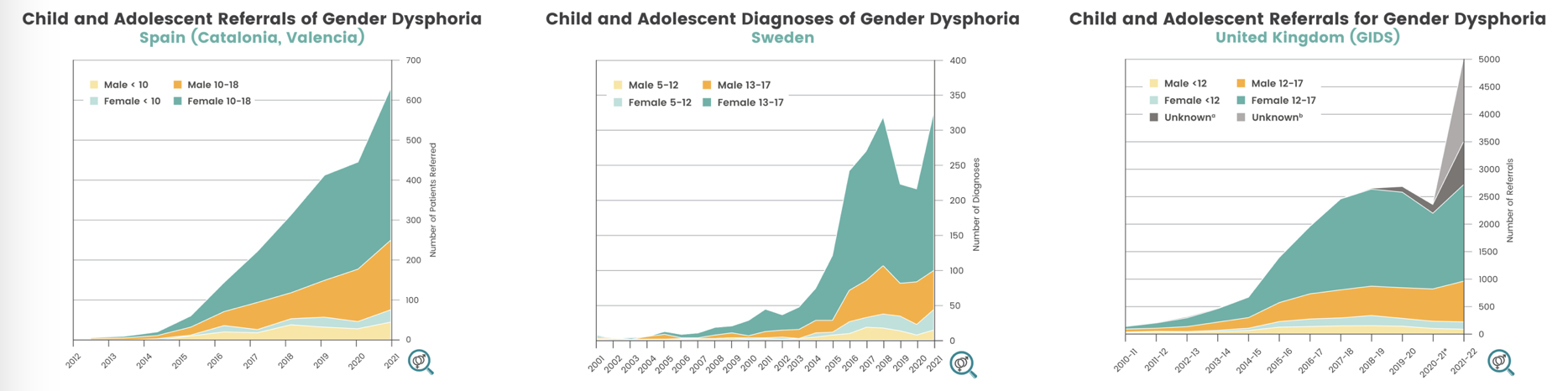

So, is anyone paying attention to these concerns? Fortunately, the answer is yes, but not so much here at home, at least not now. As The Economist put it in their cover story this week, “On different sides of the Atlantic, medical experts have weighed the evidence for the treatment of gender-dysphoric children and teenagers, those who feel intense discomfort with their biological sex. This treatment is life-changing and can lead to infertility. Broadly speaking, the consensus in America is that medical intervention and gender affirmation are beneficial and should be more accessible. Across Europe several countries now believe that the evidence is lacking and such interventions should be used sparingly and need further study. The Europeans are right.”

The Economist, 2023: What America has got Wrong About Gender Medicine

In response to the NICE report and the subsequent Cass review, the NHS announced that it is restructuring its youth gender identify services. For all youth, psychosocial counseling will be a primary emphasis. Social transitioning will not be encouraged. No medical transitioning will be offered to prepubescent children. And, for adolescents, puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones will only be made available in the context of a formal research protocol.

Sweden, Finland, and Norway have all taken comparable significant steps away from gender affirmative care, emphasizing the paucity of good data to support such care, encouraging a more cautious approach to care with a particular focus on mental health care, and generally restricting the use of medical transitioning care to research centers.

Sweden’s National Board of Health and Welfare “currently assesses that the risks of puberty blockers and gender-affirming treatment are likely to outweigh the expected benefits of these treatments. Finland’s Council for Choices in Health Care acknowledges that “research data on the treatment of dysphoria due to gender identity conflicts in minors is limited”, and that there is also a “need for more information on the disadvantages of procedures and on people who regret them.” The Norwegian Healthcare Investigation Board (NIHB) “recommends that puberty blockers and hormonal and surgical gender confirmation treatment for children and young people are defined as experimental treatment.”

France has not yet restricted access to gender affirmative care, but its Académie Nationale de Médecine urges that “great medical caution must be taken in children and adolescents, given the vulnerability, particularly psychological, of this population and the many undesirable effects, and even serious complications, that some of the available therapies can cause”. It also acknowledges social contagion as a cause of the rapid rise in referrals, stating “whatever the mechanisms involved in the adolescent – overuse of social networks, greater social acceptability, or example in the entourage – this epidemic-like phenomenon results in the appearance of cases or even clusters in the immediate surroundings.”

NHS, 2022: Interim Service Specification for Specialist Gender Dysphoria Services for Children and Young People – Public Consultation

Socialstyrelsen, 2022: Care of Children and Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria

Palveluvalikoima, 2020: Medical Treatment Methods for Dysphoria Associated with Variations in Gender Identity in Minors – Recommendation

Ukom, 2023: Pasientsikkerhet For Barn Og Unge Med Kjønnsinkongruens

Académie nationale de médecine, 2022: Medicine and Gender Transidentity in Children and Adolescents

And, notably, returning to the Netherlands, Thomas Steensma, a psychologist at the Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria in Amsterdam, has raised concerns about the increase in number of presenting youths, particularly the increase in natal females, and the paucity of data used to support treatment, most of which has come from his country.

“We don’t know whether studies we have done in the past can still be applied to this time. Many more children are registering, and also a different type. Suddenly there are many more girls applying who feel like a boy. While the ratio was the same in 2013, now three times as many children who were born as girls register, compared to children who were born as boys.”

“Little research has been done so far on treatment with puberty blockers and hormones in young people. That is why it is also seen as experimental. We are one of the few countries in the world that conducts ongoing research about this. In the United Kingdom, for example, only now, for the first time in all these years, a study of a small group of transgender people has been published. This makes it so difficult, almost all research comes from ourselves.”

Algemeen Dagblad, 2021: More Research is Urgently Needed into Transgender Care for Young People: “Where Does the Large Increase of Children Come From?”

Given the current insistence on the benefits of gender affirmative care here at home, I was pleasantly surprised to find that scientific researchers in the U.S. had taken an even earlier interest in the uncertainties regarding such care. The NIH asked the Institute of Medicine to convene a consensus committee to conduct a review “assessing the state of the science on the health status” of LGBT population writ large, and their report was published way back in 2011.

Focusing only on transgender youth, some of their findings include, “a relatively small percentage of gender-variant children may develop an adult transgender identity”, and “while GnRH analogs may be used to alleviate gender dysphoria among adolescents, a paucity of empirical data exists concerning how these medical interventions affect overall physical health and well-being” (GnRH analogs is the more proper medical name for puberty blockers). They go on to argue “there is a need for more research on the health implications of hormone use (e.g., randomized controlled trials of puberty-delaying hormones, masculinizing and feminizing hormone therapies, and the consequences of long-term hormone use).”

National Academies Press, 2011: The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People

In 2015, the NIH authorized a comprehensive study to examine the mental health and other outcomes for gender dysphoric youths treated at four gender identity clinics in the U.S. But, don’t get your hopes up; long term results will take years to accumulate, and still will not adequately address the concerns raised by the multiple government agencies and scientific panels cited above. Although this study has more participants than the Dutch studies, over 400 as of the most recent report, it is the same type of observational study, rather than the randomized control trial recommended to the NIH by the Institute of Medicine.

JMIR, 2019: Impact of Early Medical Treatment for Transgender Youth: Protocol for the Longitudinal, Observational Trans Youth Care Study